Go to A Pulp Manifesto, Version 1.0 to see how it all started.

LIKE THE BEST LITERARY FICTION, THE BEST PULP FICTION has had a profound impact on both the content and the texture of the arts in the Twentieth Century and beyond. The original Pulps grew out of their Nineteenth Century predecessors, converging at the peak of their popularity in the 1920s and 1930s with both a new direction in ‘high’ culture and arts, and with new technologies allowing for the replication and national distribution of media.

Unwittingly, Pulp took its first lungfuls of air as both Modernism and Popular Culture came to define the century. But what was the original Pulp? And how did it go on to impact ‘high’ art and become a part of the Modernist and Post-Modernist ethos? And how does “PULPable” material survive in the creative consciousness today?

THE PULP CRUCIBLE: GROWTH & CHANGE

Though the term “mass media” was coined in 1920, the previous century had seen technological leaps allowing communication, production and distribution to become cheaper and easier than ever. Photography, telegraphy and telephony, audio and visual recording technologies: all of these were in their infancy but clearly pointing the way forward. And alongside technological developments, the intelligentsia was beginning to question the social model that had held together for so long.

Where Realpolitik and the Realist movements were once the benchmarks for pragmatic thinking, now proto-Modernists like Flaubert, Manet and Baudelaire were moving into more subjective territory, presenting a more fragmented, fractured human experience.

A Bar at the Folies - Edouard Manet

Darwin’s Theory of Evolution began to undermine religious faith; Marx proposed that the capitalist doctrine was untenable; and Nietzsche’s Übermensch (Superman) in 1883 predated Hitler’s birth by six years and Clark Kent’s by 55. Man’s faith in religion, literature, and philosophy was increasingly decentred.

As the Twentieth Century got into full swing, mass media bloomed. By 1927 we had the world’s first ‘talkie’ in The Jazz Singer, and commercial radio and television was broadcasting from New York and London by the ‘30s and ‘40s. A simultaneous explosion in disruptive counter-realism paved the way in ‘high’ culture: Picasso’s Cubism and Mondrian’s lines and squares, Schoenberg’s atonal codas and Eliot’s Wastelands were all modern and Modernist by being contrary, and anti-progressive by being counter-historical. At the same time, half a century of disruption and worldwide violence were going to be made both more distant and more shocking via radio, newspapers and television.

LET ME ENTERTAIN YOU: THE ORIGINAL PULP FICTION

Whilst ‘high’ culture disseminated this social upheaval and turned political, mass entertainment and the Pulps were born. Duplication and linear production methods had finally made it cheap and easy to print books and newspapers, and by the 1830s pulp predecessors were already providing for the masses.

Victorian ‘Penny Dreadfuls’ usually focused on lurid, sensational news stories or took Gothic novels such as The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole and rewrote them for the semi-literate.

Sweeney Todd & his fellow Penny Dreadfuls

The upper classes saw them as subversive, ‘low’ nonsense, but they introduced the likes of Sweeney Todd and Dick Turpin to the general public and in pulping ‘high’ art—both literally and literarily—they predated pulp’s tendency to mix and match literature and entertainment. On the other side of the Atlantic, Beadle’s ‘Dime Novels’ appeared in 1860. Their articles were soon replaced by fictionalised accounts of frontiersmen migrating into the Wild West, though the Buffalo Bill ‘cowboy’ archetype eventually gave way to the first pulp ‘detective’ characters and ‘sleuths’.

One of the first Pulp magazines, The Argosy began in 1882 and ran until 1978. Native Mainer Frank Munsey had moved to New York City and, despite financial difficulties, managed to get his Boy’s Own rag off the ground; by 1894 it was publishing solely pulp fiction written by authors more eager to get published than to get paid. Munsey’s innovation was in combining cheap production and distribution methods to provide affordable mass entertainment, and at its peak each issue reached one million readers.

The Argosy, at its peak Pulp power

But a move in the late ‘40s from pulped to glossy paper was as symbolic as it was financial—The Argosy had gone back to its roots and was once more a non-fiction title.

Perhaps the most famous Pulp magazine (and the inspiration for Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction), Black Mask ran from 1920 to 1951 alongside a burgeoning Modernist movement and through World War II. But it was the Great War which may truly have shaped it: industrialisation and mass production had simply made it easier to kill more people more quickly, and Modernists felt that the War was an indictment against those who had advocated the cultural ‘progress’ of the Nineteenth Century. In an age before the media could define the course or motivations of a war, it was also much simpler to define the ‘good guys’ and the ‘bad guys’, and these fictional archetypes of heroism were soon transposed into the Pulps.

Black Mask, in grand pulp tradition, was started in order to cover losses for another magazine: editors H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan also published The Smart Set, whose contributors were paid much more, and which sold far fewer copies.

Black Mask staff & writers: on the back row, Chandler is second from left, Hammett is far right

After eight issues, Joseph Shaw took the editorial reins and the era of hard-boiled detective fiction began. Carroll John Daly’s story Three Gun Terry is widely considered the first in the genre, but Dashiell Hammett’s Arson Plus came in 1923 and Raymond Chandler was a late starter with Blackmailers Don’t Shoot in 1933.

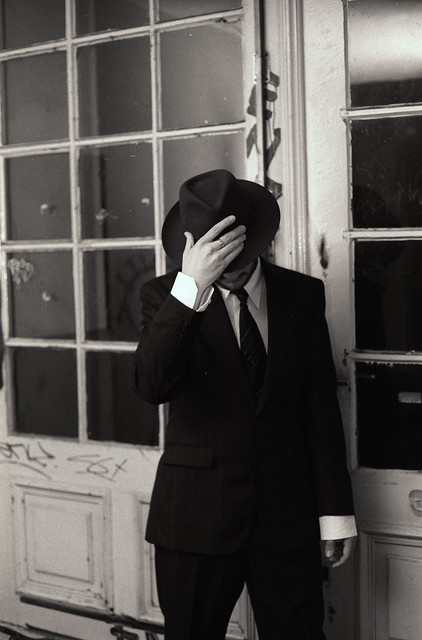

One thing that Joseph Shaw shared with his authors was a past in the armed services. They had worn their uniforms during World War I—Shaw as an officer, Chandler in the Canadian services, and Hammett as a medic—and they now wrote of urban soldiers back from battle, wearing a trench coat in place of fatigues and a fedora in place of a helmet. “Once you have led a platoon of men into machine gun fire, nothing is ever the same again,” said Chandler; Marlowe and his contemporaries were lucky enough to be up against mere gangsters and femme fatales. “Having seen atom bombs go off, [people] were ready for something a little stiffer than drawing room mysteries.”

Elsewhere, another type of uniform was being donned by altruistic detective characters turned supernatural: Doc Savage, the Phantom and the Shadow sprung from the pages of Pulp magazines into comic books.

Action Comics #1: Superman launches a wave of superhero tales

In 1938, an old strip created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster made the front cover of Action Comics, and Superman launched superheroes worldwide.

But as television, movies, radio and paperbacks took over in the 1940s, Pulps and comic books waned, while authors moved on to screenplays, long form fiction or journalism. Started in 1941, Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine survived only by attempting to combine the literary tendencies of some Black Mask authors with the need for pulp entertainment. As Modernism began to fuse with popular culture, so Ellery Queen fused ‘high’ art with the Pulps’ sense of fun.

FROM MODERNISM TO POST-MODERNISM: FROM PULP TO PULPABLE?

As the Second World War drew to a close, reality began to determine modern innovation: rations continued through the ‘40s, whilst mass production helped to rebuild ruined cities. Paper shortages during the War, coupled with the growth of television and the bankruptcy of major Pulp publisher the American News Company, brought Pulp’s heyday to an end in the late ‘50s.

But their cultural echoes—and the evolution of “PULPable” material—were near at hand. What was modern was now also popular. British ‘Mods’ listened to Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones or the Who referencing Modernist poets and poetry in their lyrics. In the United States, ‘high’ art fused with popular culture as a young Andy Warhol exhibited mass-produced,

High & low converge: Dylan at Warhol's "Factory"

multiple images of consumer items and consumed celebrities, Warhol—like Lichtenstein—using the dot-printing method that comic books and the illustrated Pulps had used.

Vietnam also became the first ‘living room war’ and paved the way for a darker, more cynical view of the black and white heroism of the Pulps. Where comic books had once been the domain of supernatural detectives, they now became more complex or more issue-driven—Stan Lee’s X-Men were a thinly-veiled allegory for the civil rights movement—whilst on television pulp echoes were similarly felt—Star Trek went boldly, and Batman went camply.

Those working in the popular spheres drew on both the new mythology of Pulp entertainment and the ‘high’ culture preceding them to create a cut-up view of the world. Central to this became self-conscious referentiality: on the one hand, Warhol’s pointillised Marilyns referenced popular culture in ‘high’ art, whilst Dylan’s lyrics about Eliot and Pound referenced ‘high’ culture in popular music. Modernism had flourished in consumer and capitalist societies, and the Warhols and Dylans were the beginning of “PULPable” artists.

The fusion of ‘high’ and pop culture brought a new, post-modernist creative philosophy: a lack of objectivity, complex and inter-referential texts and an undermining of one’s own authority via parody, pastiche and irony did away with Modernism’s central ethos. But where the Post-Modern and the “PULPable” differed was the choice of cultural yardsticks. “PULPable” creators took the comic books, movies, television shows and mass entertainment of the last half-century and jumped right in:

The Onion magazine: a post-satire world?

as David Foster Wallace put it, “about the time television first gasped and sucked air, mass popular US culture seemed to become High-Art viable as a collection of symbols and myths.”

As artists became “products of more than just one region, heritage and theory, citizens of a culture that said its most important stuff about itself via mass media,” a reference to Superman or Jimmy Stewart bore as much endowed meaning as a reference to anything predating them. And as mass media reached even more people, it became inevitable that these references would form the basis for an important arm of the creative arts.

PULP IS DEAD! LONG LIVE PULPABLE

As the original Pulps had come of age against the cultural and technological developments of the Nineteenth Century, so their “PULPable” influence has lived on in the nexus between ‘high’ and popular culture. Pulp magazines and comic books saw many ‘literary’ writers producing Pulp fiction—Tennessee Williams, Upton Sinclair, Mark Twain, and Rudyard Kipling—but also saw those such as Raymond Chandler, Isaac Asimov, William S. Burroughs and Arthur Conan Doyle move out of the popular and onto the periphery of the literary canon.

Mass production and distribution turned those authors, but also their characters, into modern-day icons, and as Modernism twisted into Post-Modernism, they became a recognisable frame of reference for the disjointed narratives presented by their successors. Though the direct descendants of the Pulps live on in the form of unironic comic books or adventure films such as Star Wars, it is the “PULPable” philosophy—Post-Modernism with a popular twist—which fuels much of the creative arts and remains most fascinating.

So somewhere in a self-conscious nexus between ‘high’ and popular culture, Alan Moore is writing a comic book about an un-hero, David Bowie is writing a song about a sci-fi novel, and Joseph Heller is writing a novel about a novelist writing a novel about a novelist. So sit back and realise that—no matter how hard you pray to Superman—there is no certainty, that—unless you are man from Mars—Pulp is your most handy frame of reference and that—if you were in a Tarantino film—this would be the beginning of article again.

DLR 02.11.08